Overlooked narratives lie at the center of Suchitra Mattai’s extraordinary artworks. A Guyanese-American artist of South Asian descent, she creates monumental installations, vibrant mixed-media compositions, and elaborate textile sculptures that spotlight the voices of women, so often erased from history, while also reflecting on the past of her ancestors, once brought from India to Guyana as indentured laborers by colonial British settlers.

Though Mattai has been devoted to art-making full-time since 2016, over the last few years, the 51-year-old LA-based artist has experienced a meteoric rise. Since 2021, she’s had a bevy of group and solo shows all over the United States and abroad. This year alone, she’s been the focus of several solo exhibitions, including ones at the ICA San Francisco, the Tampa Museum of Art, and “Suchitra Mattai: Myth from Matter,” an expansive solo exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) in Washington DC, set to be on show through January of next year. (This December, the artist is also set to have a solo booth at Art Basel Miami with her gallery, Roberts Projects.)

“So much of my work is about creating a new mythology and new heroines and celebrating and monumentalizing women’s work and labor. This show at the NMWA is very special to me,” Mattai tells W. In an exhibition that deals with themes of forgotten histories, favoring the generally disregarded viewpoints of women and people of color, nearly forty of Mattai’s mixed-media works will be shown alongside and in conversation with pieces on loan from other seminal museums in DC, by artists like Becharam Das Dutta and Jean Honoré Fragonard.

To produce her mesmerizing works, Mattai draws on a multitude of found and sourced objects that range from vintage saris, tapestries, and antique needlepoints to hair rollers, jewelry, and furniture. “A lot of my work is intuitive, and I think many artists don’t always say it, but we have visions, we see things,” Mattai says. “In the studio, I have many objects and saris sorted in colors, but I also look for objects. Sometimes, I see them and feel immediately excited, and I need to make something right away. Other times, it’s about having them around, and then one day, all of a sudden, they speak to me in a language that I understand,” she explains.

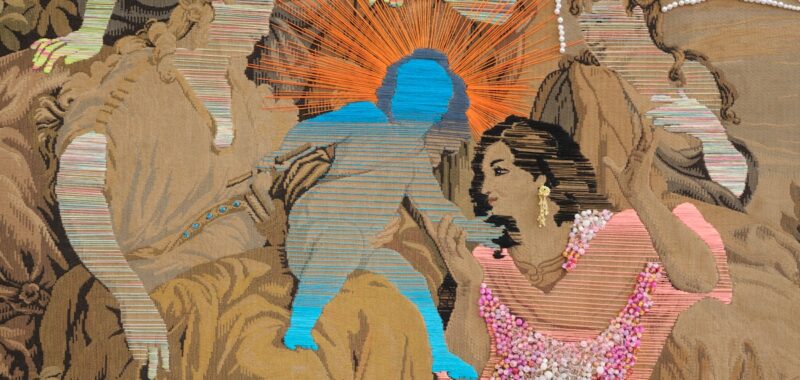

In the absence of power. In the presence of love, (detail) 2023

Collection of Julie and Bennett Roberts, Los Angeles; Courtesy of Roberts Projects; © Suchitra Mattai; Photo by Heather Rasmussen

kala pani (black water), 2023;

Private collection, Sausalito, California; Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles; © Suchitra Mattai; Photo by Heather Rasmussen

Reflecting on her increasingly flourishing practice, Mattai says moving from Denver, Colorado to her current home in LA was a major catalyst: “There’s been a building of momentum. It’s been a season of rebirth.”

Still, the road to success has not been without its stops and starts. “I always wanted to be an artist, but coming from an immigrant family, it just wasn’t something that I saw as real or possible,” she says. She opted to study statistics before pursuing an MA in South Asian Art and an MFA in Painting and Drawing at the University of Pennsylvania in the latter half of her twenties. And while she always knew deep within that she’d devote her life to art, she struggled with bipolar disorder for many years.

“I was very sick and couldn’t work for almost a decade,” Mattai recalls. “It was like being in your head for so many years and not being able to express any of it. When I came out of that, I was aching for possibilities. I had such a desire to make art, and I felt like I was making up for lost time.”

I vividly remember the first time I came across a painting by Mattai. It was three years ago at the Untitled Art Fair in Miami, and surrounded by a sea of artworks, I was transfixed by sweet surrender (2021-24), a large acrylic piece, currently on show at the NMWA, depicting twin-like mythical female figures with glowing auras embroidered atop their heads and cascading braids uniting as one cherry-colored serpent at the bottom. Mesmerized by its intricate details, I couldn’t stop thinking about it for days.

Mattai says finding her artistic footing was partially a matter of returning to her most primal, child-like desires. Growing up in Nova Scotia, she constantly drew pictures of the Caribbean, reminiscing about her early years in Guyana, where she was born and spent her early childhood. She also built her own doll houses, transformed all sorts of found objects into toys, and completed her first major art project—a large, crocheted blanket for her younger sister—at the tender age of eight.

Nowadays, this undeniable talent for embroidery and sewing, passed on to Mattai from her Guyanese grandmothers, is an essential part of her practice that she often employs to create some of her most lauded works. “One of my grandmothers was a professional seamstress, and the other made all her own dresses and my doll dresses. Both of them taught me sewing, embroidery, crochet—everything,” Mattai says.

siren song (center, installation view, John Michael Kohler Arts Center), 2022

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles; © Suchitra Mattai; Photo courtesy of John Michael Kohler Arts Center

Imperfect Isometry (2019), a piece commissioned for the Sharjah Biennial in the Emirates, was the first time Mattai created an immense tapestry by weaving together vintage saris from around the world that she assembled, displayed alongside videos of border and prison walls, a chalk drawing, and a merry-go-round.

“The idea of using saris came to me [in a vision], and it’s been a part of my practice ever since,” the artist says. “It’s very exciting because it brings communities together, and it’s a visible acknowledgment of bodies in my work.”

Since then, Mattai has employed woven saris in countless pieces, many of which are currently on show at the NMWA, such as a cosmic awakening (2023), an enormous wall tapestry composed of vintage saris, fabric, tinsel, tassels, and beaded fringe, and siren song (2022), an enthralling installation alongside a digital projection of the Atlantic Ocean, filmed by the artist herself while traveling by sea from Ghana to South America, essentially retracing the maritime journey of her ancestors.

For the rising artist, this new season of her life has also been about unlearning and connecting with materials and practices she once overlooked. “I remember in college doing embroidery and getting really mixed reactions. Most of my professors hated it, so, for years, I had all those voices in my head, as many artists do,” Mattai recalls. “When I say I had a rebirth, it was an awakening of a spirit inside of me, but also a desire to shed all these preconceived ideas and dream a different dream of what my art could be.”

This article was originally published on