For more than 40 years, you’ve been making horror movies about the human body. Shivers [1975] was about a deadly outbreak of erotomania-inducing parasites; Scanners [1981] shows telekinetic powers being used to make someone’s head explode; in The Fly [1986], a scientist accidentally merges with a housefly; and in Crimes of the Future [2022], humans have developed new organs and a fetish for public surgery. What drew you to this theme?

It had to do with an approach to life in general, an awareness that we are finite, that we are our bodies. It’s not like we are a spirit in a body—we are a body, period. Initially, I did think I would make a genre film, because in the 1970s that’s what you could get financed. I had no connection with Hollywood. I was totally a Canadian filmmaker, and there was really no film industry in Canada at that point. But I wouldn’t have anticipated that I would write something like Shivers. It just started to come out of the typewriter. It could easily have been a spy movie or a comedy.

Your latest film, The Shrouds, follows a widowed tech entrepreneur who invents a device that allows grievers to watch the live decomposition of a loved one’s entombed body. How did you arrive at making this film?

My wife of 43 years died in 2017, and I’d spent two years taking care of her. I would say that all movies are, in some ways, autobiographical. I had to deal with a character who was grieving his wife’s death. As soon as you start to write a screenplay, it’s not life; it becomes fiction. Underneath that is still everything you were feeling and your desire to untangle some complex emotions you had, but in a fictional way, which gives you the illusion of some kind of control.

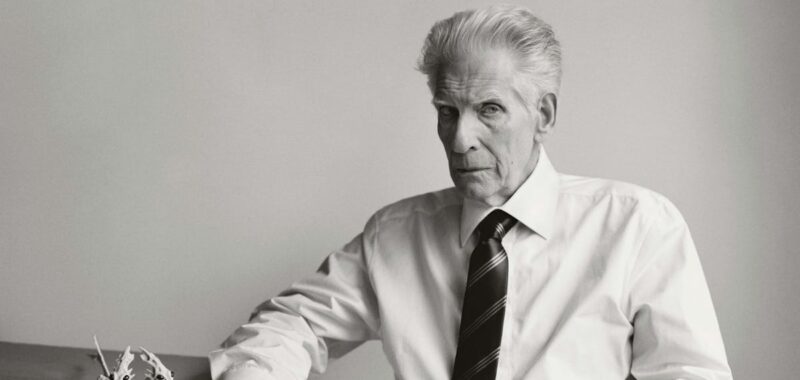

Cronenberg wears a Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello jacket, shirt, pants, sunglasses, and tie.

Many characters in The Shrouds have a paranoid fixation on collecting information about medical procedures.

When my wife was dying, a lot of people were convinced that the doctors were doing something strange, that they were maybe missing something, that the treatment wasn’t right. That’s a very typical thing, to think, Could we have done it better? Should we have taken her to some other clinic? At that point, it becomes a conspiracy theory, because you can’t prove it. It’s a desire to make something meaningful out of something that is, in fact, meaningless.

Did you always know you’d be a filmmaker?

I thought I’d be a novelist, but I was also kind of a tech nerd. I was interested in cameras and technology, and I was curious as to how movies were made. I literally looked up “camera and lens” in the Encyclopedia Britannica and figured it out. I wasn’t interested in going to film school. I was happy to be self-taught, which I am. It was the New York underground that made film accessible—Ed Emshwiller, Kenneth Anger, and the Kuchar brothers. We had a lovely cinema in Toronto called Cinecity, which showed Jean-Luc Godard and European films. We had an all-night screening of New York underground films, and Cinecity invited the filmmakers to come to Toronto. It was fantastic. As the sun came up, we came out with coffee and talked to Emshwiller about his movie.

Throughout your career, you’ve been labeled a “provocative” filmmaker. Do you think of yourself as a provocateur?

I’m always surprised at people’s reaction to my films. I was surprised at how extreme the reaction was to Shivers and, even much later, to Crash [1996], when it was called “the film beyond the bounds of depravity.” I thought, well, wait a minute! I have often explained it this way: I find some interesting things—imagistic things, conceptual things, philosophical things—and I wind them all together in some kind of narrative. I’m experimenting, I’m challenging myself. Then I say to the audience, okay, I found this and I made these interesting connections, and if you’re interested, come along with me. I didn’t do the Alfred Hitchcock thing of “I am a puppet master, and I will control all your reactions.” It was more like I was mastering myself, rather than the audience.

Grooming by Claudine Baltazar for Oribe at Plutino Group; Photo Assistant: Julius Frazer; Retouching: Color Center; Fashion Assistant: Kyla Akey.