In the last year, the Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians – Kizh Nation has worked to protect its cultural sites from more than 850 land development projects around the Los Angeles Basin, thanks to a 2014 state law that allows tribes to give input during projects’ environmental review processes.

Now, its chief fears that a newly proposed bill could significantly limit how the tribe — and dozens of others still without federal recognition — could participate.

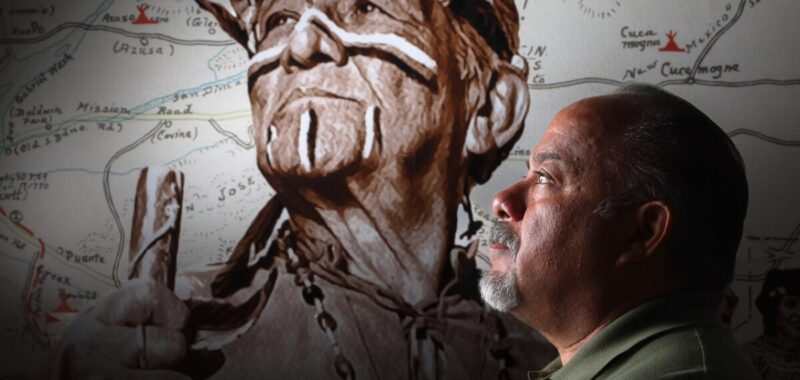

“This is an atrocity,” said Andrew Salas, chairperson of the Kizh Nation. “Let’s not call it a bill. [It’s] an erasure of non-federally recognized tribes in California. They’re taking away our sovereignty. They’re taking away our civil rights. They’re taking away our voice.”

The new bill, AB 52, was proposed by state Assemblymember Cecilia Aguiar-Curry (D-Winters) and co-sponsored by three federally recognized tribes: the Pechanga Band of Indians, the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria and the Habematolel Pomo of Upper Lake. Supporters say the amendments would strengthen and reaffirm tribes’ rights to protect their resources, granted by the 2014 law of the same name.

“This bill is about protecting tribal cultural resources and affirming that tribes — both federally and non-federally recognized — are the experts on our own heritage,” Mark Macarro, tribal chairman of the Pechanga Band, said in a statement.

But shortly after the bill was substantively introduced in mid-March, tribes without federal recognition noticed that while federally recognized tribes would hold a right to full government-to-government consultations, their tribes — still sovereign nations — would be considered “additional consulting parties,” a legal term that includes affected organizations, businesses and members of the public.

The original AB 52 is a keystone piece of legislation on California Indigenous rights, representing one of the primary means tribes have to protect their cultural resources — such as cemeteries, sacred spaces and historic villages — from land development within their territories.

The new bill would require that tribes’ ancestral knowledge carry more weight than archaeologists and environmental consultants when it comes to tribes’ cultural resources. It would also explicitly require the state to maintain its lists of tribes — including both federally recognized and non-federally recognized — that many pieces of California Indigenous law rely on.

Yet, Indigenous scholars and leaders within non-federally recognized tribes say the new differences between how tribes with and without federal recognition can participate amount to a violation of their basic rights, including their sovereignty.

They say the language could allow tribes with federal recognition to overstep their territory and consult on neighboring non-federally recognized tribes’ cultural resources.

“I don’t want a tribe who’s 200 miles away from my tribal territory to get engaged in my ancestral lands,” said Rudy Ortega, president of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians. “We know the ancestral territory, we know the landscape, we know our history.”

The bill’s sponsors say the new amendments aren’t designed to declare who deserves recognition and who doesn’t — and the difference in language is simply a reflection of the reality of which tribes have federal recognition and which don’t.

“Tribal cultural resources and the recognition of tribes as distinct political entities are fundamental pillars of our tribal sovereignty,” the Graton Rancheria and Pechanga Band tribes said in a joint statement. ”It is critical that this bill protect and reaffirm the sovereignty and government-to-government relationship between the State of California and federally recognized tribes.”

In practice, supporters say, there would be little difference between how tribes with and without federal recognition consulted with California government agencies. But for tribes without federal recognition — who argue there’s no reason to apply federal tribal distinctions to state law — that provides little comfort.

The clash began mid-March when a friend of Salas’ — also a scientist who consults on environmental reviews — noticed the language changing the status of non-federally recognized tribes amid the collections of other amendments to the process.

Salas’ friend alerted him over the phone: “Be aware, I’m telling you — look it up.”

He immediately alerted everyone in the tribe’s office in Covina. When the tribe began reaching out to other governments, it became clear the bill was unanticipated. “Lead agencies didn’t know about it; the city, the county — nobody knew about it,” Salas said.

Word quickly spread through tribal leaders across the state. None of the tribes without federal recognition interviewed by The Times said Aguiar-Curry’s office had reached out to consult them on the new bill before it was published.

“Input from federally and non-federally recognized tribes informed the bill in print,” Aguiar-Curry’s office said in a statement to The Times. “We’ve received feedback, we recognized the bill language started in a place that did not wholly reflect our intent — which is that all tribes … be invited to participate in the consultation process.”

The non-federally recognized tribes quickly began forming coalitions and voicing their opposition. At least 70 tribes, organizations and cities had opposed the amendments by April 25.

The following Monday, Aguiar-Curry announced she would table the bill until the start of 2026, but remained committed to pursuing it.

“The decision to make this a two-year bill is in direct response to the need for more time and space to respectfully engage all well-intended stakeholders,” her office said in a statement. “Come January, we’ll move a bill forward that represents those thoughtful efforts.”

Many tribes without federal recognition still see a long road ahead.

“I don’t have a huge sense of victory,” said Mona Tucker, chair of the yak titʸu titʸu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash Tribe of San Luis Obispo County and Region. “Hopefully the Assembly person, Aguiar-Curry, will engage with us, with a group of tribes that do not have federal acknowledgment, so that there can be some compromise here. Because to exclude us is a violation of our human rights.”

Salas would rather see the amendments killed entirely.

“We thank Assemblymember Aguiar-Curry for at least putting it on hold for now; however, this is not the end,” he said. “We are asking that she — completely and urgently and respectfully — withdraw the amendment.”

Government-to-government consultations are often detailed and long-term relationships in which tribes work behind the scenes to share knowledge and work directly with land developers to protect the tribe’s resources.

Last year, the environmental review process helped the Kizh Nation win one of the largest land returns in Southern California history for a tribe without federal recognition.

When a developer in Jurupa Valley proposed a nearly 1,700-house development that threatened nearby significant cultural spaces, the Kizh Nation entered a years-long consultation with the developers behind the scenes. Eventually, the developers agreed to maintain a 510-acre conservation area on the property, to be cared for by the Tribe.

Similarly, it was one of these tribal consultations that reignited the cultural burn practices of the ytt Northern Chumash Tribe. In 2024 — for the first time in the more than 150 years since the state outlawed cultural burning — the Tribe conducted burns along the Central Coast with the support of Cal Fire.

California has 109 federally recognized tribes. But it also has more than 55 tribes without recognition. That’s because federal recognition is often a decades-long and arduous process that requires verifying the Indigenous lineage of each tribal member and documenting the continuous government operations of the tribe since 1900.

And tribes in what is now California — which was colonized not once but three times — have a uniquely complex and shattered history. Since 1978, 81 California tribal groups have sought federal recognition. So far, only one has been successful, and five were denied — more than any other state.

For this reason, AB 52 and other keystone pieces of California Indigenous law — such as those that allow tribes to give input on city planning and take care of ancestral remains — use a list of tribes created by the state that includes tribes both with and without federal recognition.

Leaders of tribes without federal recognition saw the last few weeks’ AB 52 flash point as an opportunity to build momentum for greater protections and rights for all tribes in California.

“What does the world look like Oct. 10, 1492?” said Joey Williams, president of the Coalition of California State Tribes and vice chairman of the Kern Valley Indian Community. “Here in California, there were about 190 autonomous governments of villages and languages and self-determined people — sovereign people that are liberated, that are free.”

Williams helped form the Coalition of California State Tribes in 2022 to fight for that vision.

“We just want that for our tribal people,” he said. “We want them to have access to all that sovereignty, self-determination … and full acknowledgment by the federal government and state government.”